The Museum is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

All parking in and around Balboa Park now requires payment. For more information, please refer to the City of San Diego website.

History

Residing on Indigenous Land

The Museum of Us (the Museum) is located in Balboa Park on the unceded territory and ancestral homeland of the Kumeyaay Nation, the Indigenous Peoples of this land. Kumeyaay people have lived on this land for millennia, and their ancestral relationship with the land continues to this day.

Before the construction of Balboa Park, the surrounding land was not barren or deserted. The development associated with the Panama-California Exposition in 1915 dispossessed and displaced Indigenous communities living in the area to build Balboa Park.

Evolving Our Mission & Name

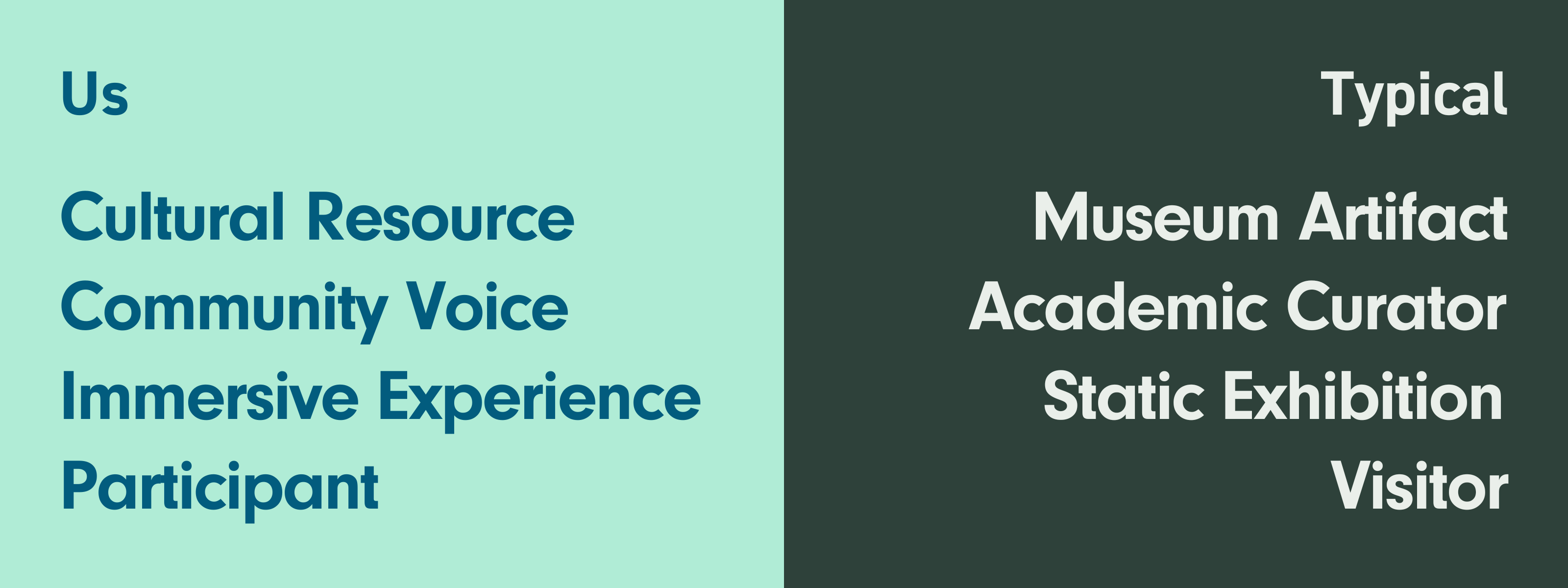

At its founding, the Museum was the epitome of an early 20th century institution of its kind; a place defined by our “collections,” of cultural resources and their traditional western European academic display. In January 2012, the Board of Directors adopted a three-year strategic plan that identified our current mission: Inspiring human connections by exploring the human experience.

The Museum has since undergone a radical transformation in policy, structure, and programming to break patterns of colonialism and build trust with our home Native American community, the Kumeyaay Nation. This shift prioritizes Indigenous and community voice, and redefines how museums steward cultural materials.

After operating as the San Diego Museum of Man for decades, we reintroduced ourselves to our community as the Museum of Us in August 2020. The change represents us holding ourselves accountable to our colonial past and present, so that we can continue to do better for our community and future generations. Our organizational practices, policies, and culture will continue to change to reflect the requests and needs of our internal and external communities. These shifts result from the guidance of our partners: elders, artists, community members, ambassadors, and scholars within Black, Indigenous, and communities of color.

Our goal is to celebrate the shared human experience through multicultural perspectives to spark dialogue, self-reflection, and human connections. Guests will come to experience a new role for museums in our community, a place that challenges assumptions and flips the idea of a museum.

History of Cultural Resources & Exhibits

When the Panama-California Exposition opened in 1915, the Museum, then called the San Diego Museum, functioned as an anthropology museum defined by its wide-ranging ethnographic “collections” – now referred to as "cultural resources" – and their encyclopedic display.

Note: We have discontinued the use of the term “collections” to describe the items the Museum stewards and the associated department. The term “cultural resources” recognizes the cultural communities from which items originated rather than the individuals who acquired, or collected, the items. The term also acknowledges the significance around how these items are a resource with deep connections to a community’s ancestry, heritage, and cultural preservation.

The Museum’s inaugural exhibit in 1915, “The Story of Man Through the Ages,” amplified the dominant Western narrative of the time – that race was biological and that societies had a hierarchical “fitness for survival” based on race.

Other foundational exhibits of the Museum presented Indigenous communities and cultures as civilizations frozen-in-time and peoples of the past. This one-sided narrative elevated Euro-American academic perspectives above the voices of Indigenous communities relative to their past, present, and future. These narratives perpetuated racism against People of Color and the erasure of Indigenous peoples, contributing to systemic inequities that persist today.

The Museum holds over 75,000 documented ethnographic cultural resources; 350,000 archaeological cultural resources; 50,000 photographic images; 300 linear feet of archival materials; and approximately 7,000 Ancestors from a global community. Most cultural resources are of Indigenous origin, with more than 200 Indigenous communities represented from within the United States and over 200 Indigenous communities internationally.

Over the course of its history, the Museum acquired the bodies and belongings of Indigenous people, in the United States and globally, in ways that were legal but unjust or inequitable. For a vast majority of our acquisitions, the transactions that caused belongings to leave Indigenous communities are often obscured by a lack of transparent or available documentation in our records.

Today, we recognize that the vast majority of these cultural resources came to us through inequitable and colonial pathways. We are committed to decolonization and to the repatriation of Ancestors and cultural resources in accordance with NAGPRA federal law and our Colonial Pathways Policy.

We also recognize many of our past exhibits – including our foundational exhibits – are deeply problematic. We seek to redress the harm caused by these exhibits through a variety of initiatives, both internal and external, that prioritize anti-racism and decolonization - a long-term process meant to undo institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms which reinforce racial group inequity, especially in regard to Indigenous Peoples.

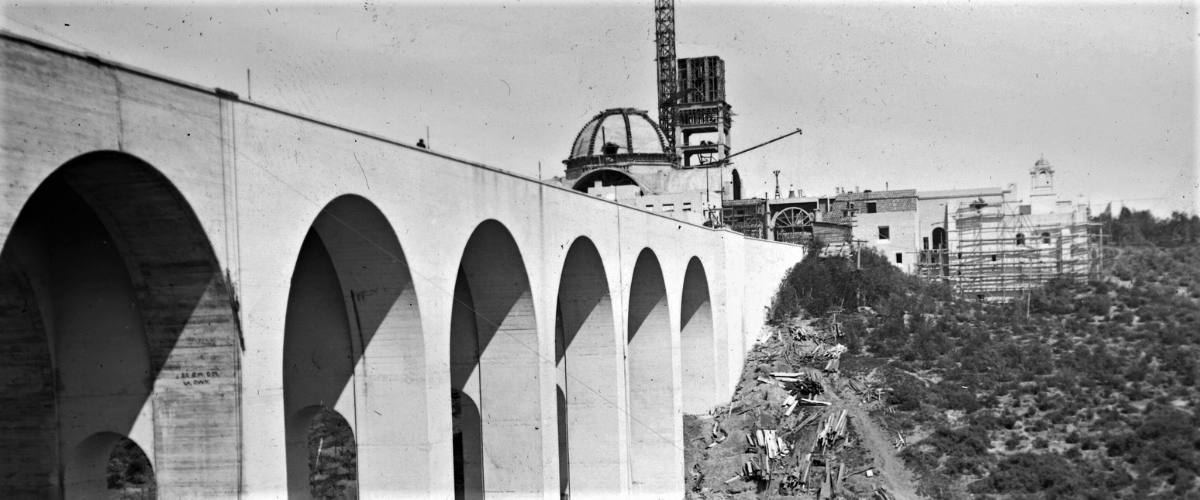

Our Home - The California Quadrangle

In 1915, San Diego celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal with a grand exposition in the newly opened 1,200-acre Balboa Park. The Park was filled with an array of Spanish Colonial Revival style buildings and Mediterranean inspired landscapes and gardens – all meant to promote California and San Diego as centers of commerce and culture.

The Park’s featured construction was the California Quadrangle, which was comprised of the California Building, California Tower, and three wings which surround the California Plaza. Created as the entry point to the exposition and designed by Bertram Goodhue, this iconic complex of buildings blends a flamboyant combination of architectural styles for a unique interpretation of Spanish religious architecture.

Bertram Goodhue's design is a significant representation of structures that commemorate the Spanish legacy of colonization in the Americas. Our architecture is deeply rooted in the complex colonial history of San Diego, with sculptures of conquistadors and missionaries on the façade while Indigenous Peoples are conspicuously absent.

Resources

- Learn more about the Panama-California Exposition from the San Diego

History Center. - Learn more about the history of the California Building from Richard Amero and the San Diego History Center.

- Learn more about the colonial legacy of the California Building’s façade, and the European colonizers depicted on it.

The Museum of Us recognizes that it sits on the unceded ancestral homeland of the Kumeyaay Nation. The Museum extends its respect and gratitude to the Kumeyaay peoples who have lived here for millennia.

The Museum is open daily, Monday through Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

1350 El Prado, San Diego, CA 92101